Lucknow is perhaps best known today for the many Islamic monuments dating from the time of the Nawabs, Muslim royalty who ruled over the city until they were deposed by the British in 1856. The city was the capital of Avadh a princely state that broke away from the Mughal Empire in the mid eighteenth century. It became a centre for the arts with many poets, singers and dancers gaining fame there. It also became an important centre for Shi'a Islam, something that continues until today and which can be seen in the annual Muharram processions and events. Today it is the capital of Uttar Pradesh, India's largest state and home to about 4 million people, although a range of figures can be found for its population.

A busy, bustling place, in 2015, Lucknow was named as India's second happiest city. Residents gave numerous reasons for this, including improvements to the infrastructure, cultural activity, parks, great food and most of all, the helpful and friendly people. I spent a few days there earlier this year and can attest to much of this but the place I most enjoyed was a long, narrow street known as Chowk. There are more than 5000 businesses in this street and the narrow lanes leading off it and you can find just about anything here. Hundreds of small food outlets sell the city's famous kebabs, and there are countless chai stalls and some excellent sweet shops. The Chowk is also home to businesses dealing in traditional crafts including the famous Chikan (embroidery), jewellery, wooden items and attar - essential oils and perfumes made from flowers. In addition to this, some of India's disappearing arts and traditions can be seen in the Chowk but mass production, foreign imports and changing social attitudes are inevitably placing pressure on a number of small, mainly family run businesses.

Ejad Emaz' family have had a kite shop in the Chowk for more than 100 years. He is 60 years old and has worked in the shop since he was 20. His colourful kites are made by homeworkers who then bring their work to him for sale. He has both male and female workers but says that the women are more efficient. All of the kites are made in the traditional way, from paper rather than the modern plastic versions imported from China. Kite flying is still popular in India, both throughout the year and at special times such as Independence Day and during religious festivals. Ejad told me that although business is rather less than in the old days, it is still enough to survive at least for the time being.

Mohammed Ibrahim Warsi is 65 years old. His family have sold surma in the Chowk for more than a century. Surma, sometimes called kohl, is a traditional cosmetic used as a type of eyeliner by both men and women. Made from various ingredients, it generally includes sandalwood paste, castor oil, ghee and soot. Some communities believe it to have medicinal properties whilst there is also a belief that it prevents children from being cursed by the evil eye. In the 1990's health concerns were raised about surma when high concentrations of lead content were found in some products. This can cause lead poisoning and a range of other symptoms. Ibrahim assured me his products were healthy and beneficial. His shop was not in good physical shape and it seemed that business was not good. Despite this he was eager to talk and insisted I drink chai with him. He proudly told me that he had six children, three boys and three girls. As well as Hindi and Urdu he speaks some English learned some years ago at Hussainabad Intermediate College.

72 years old native Lucknawi Haji Sahib Sikkewale (real name Abdul Khalid) sells antique coins. He saw me before I saw him and he waved me over. He wanted to show me a newspaper article that included a photograph of him and more importantly that identified him as having a bit part in the next Amitabh Bhachchan film. Not only this, the Bollywood superstar had also bought 20 coins from him, result happiness. As well as coins, Haji Sahib sells rings and small metal objects. I noticed that like many of the neighbouring shopkeepers, he chews paan whilst waiting for customers. Paan, a combination of betel leaf and areca nut is chewed for its stimulant effect and is popular throughout Southeast Asia and the India subcontinent. It is often mixed with a lime cream and tobacco. Regular users are easily identifiable from the red stains on their lips, teeth and tongue caused by the red liquid released when chewing. Depending on the mixture, it can have a serious impact on health, destroying teeth and being linked to cancer. Some reports say that use is now decreasing but it can still be found almost everywhere including in the Chowk. In some countries the sale of paan is now banned. Many people depend on the industry for their living, including Mohammed Ali, a paanwallah who has a small stall outside one of the street's mosques. It is hard to know how people like Mohammed would survive if this happened in India.

|

| Faizan, spinner |

Lucknow is famous for its textiles and brightly coloured garments can be seen throughout the Chowk. In the past the bright yellows, reds and oranges were achieved through using only natural dyes. Today there is significantly more use of chemicals to achieve these colours but there is still enough demand to support a few shops selling natural dyes. Mohammed Shami has a shop selling only natural products and at the time of my visit was so busy that he had to continually break off talking to serve customers. His neighbour, a young man called Faizan also as a traditional business - spinning.

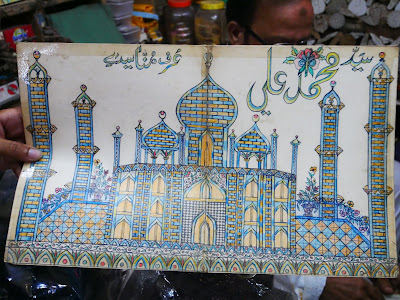

I have already mentioned Mohammed Ali the paanwallah. He has a namesake aged 58 who sells wooden printing blocks for use in hand printing designs on the Chikan garments. He has managed this small business, established 75 years ago, since his father died. He has two sons one of whom will eventually take over the business and another one who will study for a profession. This Mohammed Ali is a talented self-taught artist. Between serving customers and managing the business he produces designs for clothing, draws pictures of the city's architecture from memory and practises Islamic calligraphy. He only studied until the end of elementary school and has no formal training. A little shy at first he was very happy to show his work to me and like several of his colleagues, sent for tea so that we could sit and talk. He produces art only for his own satisfaction and does not use it commercially.

The Chowk has many delights, treasures and secrets. Some of them are being lost as traditional methods are overtaken by rapid modernisation, mass production and changing tastes. A number of shops have already fallen victim to the wreckers' ball as older buildings are demolished to make way for new developments which often lack character despite the advantages of air conditioning and other technologies. Change is inevitable but at least for the moment, Lucknow is managing to sustain many of its traditional businesses too. Maintaining this balance might well help the city retain its status as a "happy city" and to attract new visitors.

The Chowk has many delights, treasures and secrets. Some of them are being lost as traditional methods are overtaken by rapid modernisation, mass production and changing tastes. A number of shops have already fallen victim to the wreckers' ball as older buildings are demolished to make way for new developments which often lack character despite the advantages of air conditioning and other technologies. Change is inevitable but at least for the moment, Lucknow is managing to sustain many of its traditional businesses too. Maintaining this balance might well help the city retain its status as a "happy city" and to attract new visitors.

|

| Mohammed Ali, artist and seller of printing blocks |

You can see more pictures from India here.